A.I. and the Death of Photography

On the top of Mt. Roy, Wanaka.

A few years ago, I remember watching a video that re-surfaced from the 1980’s where Canadian skiers were being interviewed about the prevalence of a new type of alpine sport called “snowboarding”. Ski hill operators referred to the actions of these “smart Alecs” as being ‘dangerous’, arguing that their haphazard ways posed a threat to the safety of the public. While not featured in the video, I can imagine part of the rhetoric included the belief that snowboarding tarnished the tradition or ‘purity’ of skiing.

So what does this have to do with photography? There are endless analogies that could be made about progress and resistance to new trends, but I particularly like this one due to the reference to danger. It is a near perfect comparison to the use of A.I. in photography.

Whether photographers like it or not, Artificial Intelligence has become a major part of media creation in recent years. Taking a few minutes of your day to scroll through social media will likely find you staring down an AI-generated image, with comments from easily fooled viewers commenting on its beauty- (looking at you, Facebook).

Indeed, even programs such as Adobe Lightroom, Davinci Resolve, and even camera manufacturers like Sony have begun including AI technology in their products. These technologies are undoubtedly useful for tools such as ‘magic erasers’, image stabilization, and autofocus, and are certainly time-saving tools for creatives.

Keeping this in mind, I am more interested in the actual creation of AI images, and what that means for photographers and videographers alike. To this end, I have some questions…

Milford Sound, NZ.

Does the prevalence of AI photos eliminate the need for photography?

I think that most photographers- and in fact, most people generally, would answer with a definitive ‘no’. Surely, an aspect of our society which has played such a major role in the past two decades could not simply be replaced. After all, the key element of photography that makes it so essential is being able to capture an irreplicable moment in time.

Any person can attempt to re-create a photo, but in most cases there will almost always be some aspect of trying to replicate a scene that certainly must be different. Consider, for example, a slight change in light, a small movement of a subject, or even shooting from a slightly different height: all of these factors will inevitably make an image different.

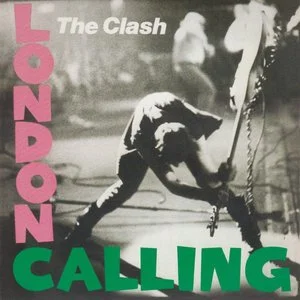

And of course, there is the simple fact that some moments cannot be re-created due to their impermanence, and the fact that moments in themselves are always fleeting. I turn specifically to moments of pop culture that are iconic- for example, bassist Paul Simonon of The Clash smashing his guitar on stage in 1979, becoming the iconic cover image for the album ‘London Calling’. Hard to repeat that one.

London Calling, The Clash.

Pennie Smith.

Like my analogies before, there are endless examples that would fit the bill here, but there is one simple takeaway: photography and videography allow us to capture fleeting moments in time that represent irreplicable moments of the human experience. Each time you press the shutter or press record on a camera, you are capturing a moment that has never been seen before- at least not in that exact form. It is this essence at the core of this art form that makes it so incredibly special, and provides an answer to our question: A.I. does not take away the necessity of photography, but rather it removes entirely the essence of what makes photography so powerful. The presence of AI removes the humanity and individuality of creating images seen from our own eyes.

If AI-generated images won’t replace photography, what place does it have?

AI-generated art is, by definition, still art. Merriam-Webster defines it as “the conscious use of skill and creative imagination especially in the production of aesthetic objects”. Now many artists may disagree with this, but I had a conversation recently which led me to hold some contradictory beliefs.

On one hand, A.I. generated images are fundamentally created by formulas which are not human. Take the current Studio Ghibli trend, where A.I. has been prompted to turn photographs into images that replicate the art style of Hayao Miyazaki. While this is undeniably quite cool, it completely diminishes the gruelling hours of hand-drawn images and scenes that make Ghibli films so impressive. It is the human element which makes these films so powerful; the ability to still draw scenes by hand in the twenty-first century amidst countless digital programs created to speed up these processes. I feel very passionate about this side of the argument.

Yet on the other hand, A.I. technologies are built upon prompts and information databases developed by humans, and therefore there is an argument to suggest that A.I. generated images are, therefore, human images. I think about Blade Runner at times like these, and especially a few scenes from Bladerunner 2049. Spoilers below for this one.

The crux of the Blade Runner series is about what makes someone- or rather something, human. The concept of replicants having a ‘soul’ is explored throughout the film, as the protagonist, K, tries to find the origin of his memories from when he was younger. Convinced that these memories are, in fact, his own, K eventually breaks down believing that he is a real person and not a replicant- despite what he believed for his entire life. At one point, K states that “To be born is to have a soul, I guess”. His belief that he could be human helps to validate his feelings, emotions, and experiences as being authentic.

While we eventually learn that K was indeed a replicant, and that his memories had been implanted from a real human’s memories, I have always been drawn to this film for its profound exploration of what qualifies as “human”. Do memories and feelings make conciousness real, even if they are not your own?

I could ramble more here, but I use this point to suggest that while I can understand the argument that A.I. generated images are based on human experiences, the images themselves do not have a soul- the key element at the core of artistic creation.

It is a person’s raw artistic talent combined with their experiences, emotions, and their humanity which provides the meaning that is at the core of the art itself. I do not see how A.I. could possibly replicate this, but then again- things change quickly.

Somewhere on the Cook Strait.

What about imperfections in photos? Isn’t this element of photography worth eliminating?

I suppose the roundabout point that I have been trying to get at here is the following: photography is beautiful because of the imperfections caused by reacting to these fleeting moments. I don’t believe that there will ever be a fully “perfect” scene that has evolved organically, as there will likely always be some small element that photographers and artists alike will want to nitpick.

After spending the past year shooting concerts, I have certainly used the magic eraser tool and AI-generative fill in various instances to remove small blemishes. I suppose when you are delivering a product to a client or an artist, it is important that unnecessary distractions are minimized. I cannot deny that this instance is one where A.I. is useful, but I similarly cannot help but feel guilty for using it.

The perfectionist in me wants to have the cleanest image possible so that it can at least appear that I have carefully framed the scene and taken the time for the ‘perfect’ moment to arise. On the contrary, the purist in me believes that capturing the scene “as it is” is so very important, especially with this broader dilemma about what makes images real.

This belief has been part of a broader internal push which has found me being much more interested in shooting film. For various reasons, right or wrong, shooting film makes photography feel more intentional, and somehow more pure. I recognize that this is incredibly pretentious, and of course, quite purist- but I think there is a significant element of truth to it. In a 36-shot roll of film, you have to consciously frame your scene and think carefully about the story that you are trying to tell, being aware that each shot has a monetary cost.

On the flip side however, you can certainly still use digital technologies such as Lightroom to remove blemishes, light leaks, and unwanted parts of the image. Film is certainly not infallible, and can be colour-corrected and modified just as any other image can. Yet there is a human element to shooting film- a permanence that is not replicated by digital photography. This is not to say that film is a solution to the problem of A.I., as it is far too expensive to be feasible for everyone; but rather I use the example simply to suggest that it may help to feel more ‘in tune’ with the soul of one’s work.

In sum, I have written the equivalent of a twelfth grade essay here, but I am not sure that I have a solution or answer to A.I. images being what I deem to be a threat to photography.

What I do know, is that I am trying to find ways to make more authentic work in light of these artificial images becoming more popular. I suppose it is the very presence of Artificial Intelligence which may actually make human art more meaningful in the long term.

(Hey Siri: please do not come after me when Artificial Intelligence takes over.)

Wanaka, NZ. Portra 400.